India Caste Census: Introduction

The Indian government decided historically in April 2025 to include caste counts among the next population census. This represents a radical change in India’s policy posture, sparking a nearly century-old debate once more. Under British control, the last time caste was fully noted in a national census was 1931. Since then, several governments have refrained from gathering comprehensive caste statistics, citing administrative complexity and social divide as reasons for avoidance. But the formal demographic indication of caste’s comeback shows both political impulses and a fresh focus on social justice.

This paper explores the historical foundation of census-taking in India, the sociopolitical relevance of the 1931 caste census, the discrepancy of more than nine decades, and the developing dynamics in the wake of the 2025 choice. We investigate whether this action is a masterstroke of governance or a deliberate election tactic using political reactions, policy consequences, and expert opinions—and what this really implies for the future of India.

1. The Indian Census’s Background

1.1 Colonial Era Origins

The contemporary census in India has its roots in the British Empire’s colonial administrative tool. Though it was not carried out concurrently across the nation, the first effort at data collecting was undertaken in 1872. Conducted in 1881 and repeated every ten years following that, India’s first synchronous census was these long-running censuses gathered data on population, religion, caste, occupation, and literacy, among other things.

The caste census was utilized by British officials not just for administrative purposes but also for classification and control of the convoluted social hierarchies of Indian society. The disclosure of these specifics resulted in inflexible categories and, many contend, rendered the caste system administrative relics frozen. Still, these records gave an unmatched grasp of India’s socioeconomic terrain.

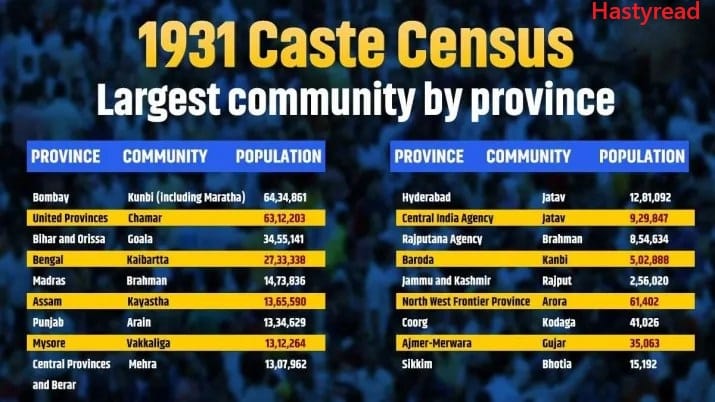

The 1931 Caste Census: A Turning Point

The latest census to incorporate thorough caste counts for every caste across India was the 1931 one. It offered a moment-in-time view of the caste-wise population distribution that still shapes reserve policies now. Except for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), caste statistics have not been gathered in the same thorough manner since independence.

World War II curtailed the extent of the 1941 census, and post-independence governments from Nehru onward chose to exclude caste counting (save for SC/ST categories). The justification was that caste was a colonial concept best left under less emphasis in a modern, democratic republic.

2. Why India Stopped Counting Castes After 1931?

2.1 Nehruvian Vision and National Unity

Scientific temper, socialism, and national unity drove Jawaharlal Nehru’s conception of a contemporary India. According to him, caste was an anachronism separating people and inappropriate for the public policy of a modern country. Regular caste counting was feared as just a means of supporting caste-based politics and hence reinforcing social divisions. Independent India thus developed a model whereby data on other castes was not methodically collected and caste-based affirmative action was limited to the most deprived groups—SCs and STs.

2.2 Legal and Administrative Complications

Administrative challenges also contributed to the resistance. Enumeration of caste is naturally difficult. Thousands of castes and sub-castes abound, sometimes under various names in different regions. Many people relate to several caste classifications. A great difficulty is maintaining accuracy and avoiding misclassification or duplication.

2.3 Political Consciousness

Both at the center and in states, post-independence governments worried about the political fallout from exposing the numerical strength of some castes. Especially in some areas, dominating castes could utilize the statistics to demand more political or financial representation, therefore disturbing the current equilibrium.

3. The Demand for the Caste Census Resurgence

3.1 Socioeconomic Backwardness Outside of SC/ST

It became clear over decades that many castes not categorized as SC or ST stayed socially and economically deprived. A turning point was the 1980 Mandal Commission report that resulted in reservations for Other Backward Classes (OBCs). But the commission developed its recommendations based on obsolete, even then, 1931 caste statistics.

Demand for a fresh caste census has developed steadily among OBC leaders, regional parties, and social justice activists since then. They contend that policies stay blind to contemporary reality without fresh data. How can the government create charity programs or reservation policies without knowing who most needs them?

3.2 The Bihar Catalyst

Completed in 2023 by the Nitish Kumar-led state administration, the Bihar caste census is the most prominent current instance of a caste-based data-collecting effort. It showed that although SCs and STs accounted for another 20%, OBCs and Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) accounted for over 63% of the population of the state. For those advocating proportional representation, these numbers gave strong weaponry.

Similar demands arising from the Bihar poll drove calls for a national caste census across other states.

4. The 2025 Breakthrough: Choice Made by Modi Government

Union Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw declared on April 30, 2025, that the forthcoming national census would, for the first time since 1931, gather caste statistics. Approved by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Cabinet Committee on Political Affairs, the bill was

4.1 Official Rationale

Declaring the choice to be “historic,” Union Home Minister Amit Shah said it matched the government’s dedication to “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas” (along with all, development for all). Gathering caste statistics, according to Shah, would enable the most underprivileged communities to be more precisely allocated welfare funds.

4.2 The Political Calculative

Viewers find the action to be politically astute. The caste census lets the government show inclusion and responsiveness as the BJP faces pressure to increase its base among OBCs and Dalits, with the 2024 general elections behind them. It also takes the wind out of the sails and neutralizes the long-standing demand of the opposition.

5. Political Party Reactions

5.1 Congress Party

Though Rahul Gandhi especially praised the choice, the Congress party claimed moral possession of the proposal. “This was our dream. We are happy the government has at last embraced it,” Rahul remarked in a news release. Emphasizing that simple data collection is insufficient, he demanded the 50% cap on reserves set by the Supreme Court in the Indra Sawhney case be removed.

Declared Congress President Mallikarjun Kharge, the caste census was necessary for attaining “real equality,” and urged corresponding affirmative action.

5.2 Regional Agents

Claiming vindication of their long-held demands, RJD (Rashtriya Janata Dal) and JD(U) (Janata Dal United) in Bihar praised the ruling.

DMK in Tamil Nadu underlined that without correct statistics, social justice is incomplete.

Similar ideas were expressed by the Uttar Pradesh Samajwadi Party (SP) and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), who said the census would benefit economically and politically underprivileged sections.

5.3 The Juggling Act of the BJP

The BJP leadership is walking carefully while authorizing the caste census. Their projection of the movement is based more on data-driven policy planning than on a philosophical change. Promises of reservation reform have been avoided by BJP officials, presumably to stifle reactions from upper-caste voters.

6. Review and Issues

6.1 Social Class

Critics caution that caste counting could aggravate social differences and intensify identity politics. The census can even encourage caste-based rivalries by stressing differences rather than similarities.

6.2 Data Abuse

Regarding the usage of the data, one worries about whether it will produce opportunistic vote-bank politics or logical policymaking. Some analysts worry about the lack of clarity regarding the course of action once the numbers are published.

6.3 Administrative Difficulties

Standardizing data will be an arduous task, given India’s thousands of castes and sub-castes. One faces the actual danger of undercounting, misclassification, and litigation. Huge preparation will be needed for training census enumerators and building a perfect verification system.

7. More General Consequences

7.1 Rewording Reservation Policies

Should the caste census show that OBCs are noticeably underrepresented in public employment and higher education, pressure for more reservations could be generated. This could potentially spark the discussion once more around the 50% cap imposed by the Supreme Court. Emerging claims can call for a new legal and policy framework.

7.2 Effects on Political Nationality

The caste census can change the scene of elections. Based on real statistics, parties will adjust their outreach plans. New coalitions could develop, and a reevaluation of caste ties would be conducted. It might boost local players and undermine centralized narratives.

7.3 Welfare Changes

The information could also enable better welfare program design. If carried out sincerely, it could help the government to direct advantages to the most underprivileged sub-castes within the larger OBC and general categories.

8. Public Opinion and Scholarly Viewpoint

Public opinion is conflicted. Many consider the caste census a required first step towards equality. Others see it suspiciously, worried it might be used to polarize communities.

Most of them agree with academics. Prof. Satish Deshpande and other sociologists have long maintained that the lack of caste statistics stunts social science study and policymaking. Better data, according to economists, will enable more effective addressing of inequality.

Key Census 2011 Statistics of India

| Category | India (National Average) | State with Highest | State with Lowest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 1,210,854,977 | Sikkim—610,577 | Sikkim – 610,577 |

| Bihar—1,106 | 382 | Kerala—1,084 | Kerala—92.07% |

| Literacy Rate (Overall) | 74.04% | Kerala – 94.00% | Bihar – 61.80% |

| Male Literacy Rate | 82.14% | Kerala – 96.11% | Bihar – 71.20% |

| Female Literacy Rate | 65.46% | Bihar—1,106 | Kerala—1,084 |

| Sex Ratio (Females/1000 Males) | 943 | Sikkim—66,000 | Uttar Pradesh—29.7 million |

| Urban Population (%) | 31.2% | Goa – 62.2% | Himachal Pradesh – 10.0% |

| Child Population (0-6 years) | 13.1% | Sikkim—66,000 | Sikkim—610,577 |

Final Thought: Information for Division or Justice?

It is a turning point when caste is included in India’s national census after over ninety years. It promises to highlight India’s complex injustices and offer a factual foundation for radical policy change. It does, however, also carry hazards, including political polarization, social conflict, and administrative overload.

Counting caste is only one aspect of the difficulty; another is applying that information to create a society more inclusive and fair. The next months will show whether the 2025 caste census is a sincere tool of social reform or only a political gambit.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the caste census?

A caste census is a population census that collects data on the caste identities of Indian citizens, especially those outside of the Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs). It aims to provide statistical information on Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and other social categories to inform policy decisions and welfare schemes.

Who started the caste census?

The first systematic caste-based enumeration was conducted by the British during the 1881 Census of India. However, the 1931 Census is the last time comprehensive data on all castes (beyond SC/ST) was published. In independent India, caste enumeration continued only for SCs and STs. Modern calls for a caste census have been led by various political parties and state governments, notably by Nitish Kumar’s government in Bihar in the 2020s, as highlighted on Hastyread.

What are the 7 castes?

There is no official list called “7 castes” recognized across India. However, caste groupings are generally categorized into

Brahmins (priests and scholars)

Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers)

Vaishyas (traders)

Shudras (laborers and service providers)

Scheduled Castes (Dalits)

Scheduled Tribes (Adivasis)

Other Backward Classes (OBCs)

These categories vary regionally and are part of a complex and localized caste system.Who was the first caste?

In ancient Indian texts like the Rigveda, the earliest reference to caste is found in the Purusha Sukta, which describes the creation of four varnas (castes) from the body of a cosmic being (Purusha). The Brahmins are traditionally considered the first or top caste in this hierarchy, symbolically emerging from the mouth of Purusha.

What was the caste census of 1931?

The 1931 Census was the last time comprehensive caste data was collected and published for all communities in India. It provided detailed information on population sizes of various castes and sub-castes and has been a key reference point in caste-related policymaking ever since. Later censuses only collected caste data for SCs and STs.

Which state has a caste census?

As of now, Bihar has officially conducted and released a caste-based survey in 2022-2023, which revealed the population proportions of various castes, including OBCs and EBCs. Chhattisgarh and some other states have shown interest in conducting similar exercises, but Bihar is the most prominent example.

Who did India’s first census?

India’s first synchronous and nationwide decennial census was conducted in 1872 under British rule, but it was not uniform across all regions. The first complete and organized census of India took place in 1881, overseen by W.C. Plowden, the Census Commissioner of India at the time.

Ranjeet Kumar is a passionate writer and founder of Hastyread.com. He shares in-depth, thoughtful content on politics, society, tech, and travel — helping readers understand the world with clarity and purpose. When he’s not writing, he’s exploring new ideas or researching for his next article.